Free childcare was the promise. Today’s announcement is the beginning. And the Test.

Today, New York took a significant step toward reshaping how families experience work, parenthood, and economic survival.

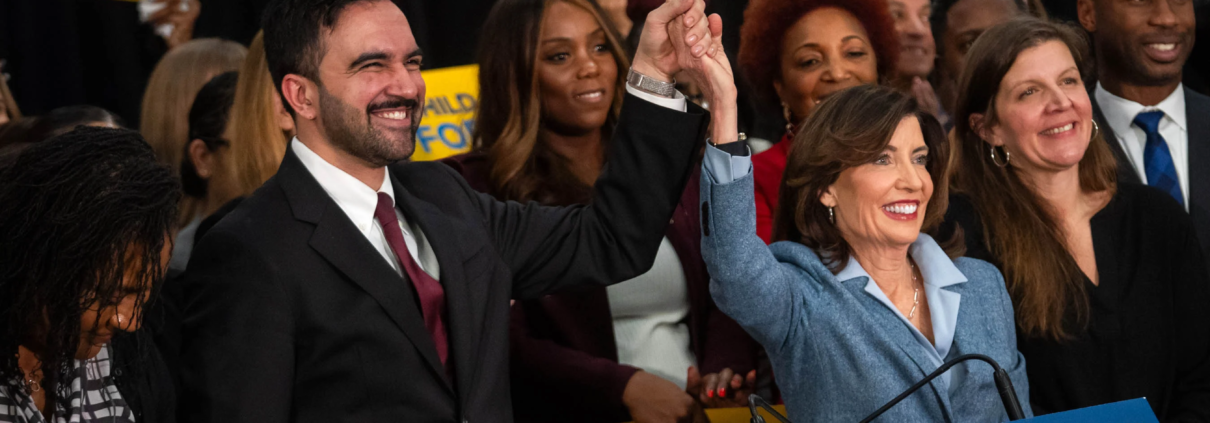

Governor Kathy Hochul and Mayor Zohran Mamdani announced a plan that would give New York City parents access to free childcare for 2-year-olds, marking a major expansion of the city’s early childhood education system and building on the existing universal Pre-K model. Governor Hochul has committed to fully funding the first two years of the program. The rollout will be phased, beginning in “high-need areas” before expanding citywide by the program’s fourth year. Hochul has also pledged to pursue a broader statewide free childcare initiative in the future.

For Mayor Mamdani, the announcement carries particular political weight. Making childcare free was one of his most visible and consistent campaign promises, and this plan represents the first concrete step toward delivering on that vision just days after taking office. In his words, the initiative is meant to demonstrate how government can “serve working families” more effectively and make New York a more affordable place to live.

The motivation behind the policy is hard to dispute. As Hochul put it, “the cost of childcare is simply too high.” Anyone who lives in New York already knows this. I know parents who want to work more hours, accept promotions, or return to school but cannot make the math work. I know single mothers who structure their entire lives around childcare availability. For many families, childcare is not just another bill, it is the gatekeeper to economic participation.

From that perspective, free childcare is a powerful and necessary idea and that is why why many New Yorkers responded positively to Mamdani’s promise. But ambition alone does not guarantee success. Implementation does.

The economic reality behind free child care New York

Free childcare for families does not mean free childcare to provide. Behind every childcare slot is a provider, often a woman, often an immigrant, frequently operating a home-based daycare with strict child-to-staff ratios, long hours, and real liability. Under this new system, many of these providers will effectively become contractors for the city, subject to fixed reimbursement rates, increased oversight, and higher expectations.

The risk is not theoretical. If reimbursement rates do not reflect the real cost of care in New York City: rent, food, insurance, labor, inflation; then the system will survive only by relying on underpaid or unpaid labor. That is how well-intentioned social policy quietly shifts its costs onto the very people delivering it.

A childcare system that depends on sacrifice rather than sustainability will eventually burn out its workforce, reduce quality, and shrink supply. That helps no one. If this program is to last, providers must be able to pay themselves, hire help when required, and operate without living on the edge of collapse. Otherwise, “free childcare” risks becoming free only because someone else is quietly absorbing the cost.

Free child care and the risk of excluding working families

There is another concern that deserves equal attention, and it requires nuance, not caricature. When officials say the rollout will begin in “high-need areas,” this often translates into strict income-based eligibility. In practice, this can mean that families with little or no declared income are prioritized. In many cases, this is entirely appropriate. People lose jobs. Families go through crises. Some parents are in transition, rebuilding, retraining, or genuinely struggling despite effort. Those situations deserve support, and no serious discussion about fairness should dismiss that reality.

At the same time, we cannot ignore how this system functions in practice over the long term.

In New York City, individuals with very low or no declared income often already have access to multiple forms of assistance — food stamps, cash assistance, subsidized or free housing, healthcare coverage, and other support programs. Meanwhile, parents with moderate earning, working full time, paying rent at market rates, receiving no housing assistance, no food assistance, and limited tax relief are frequently deemed “too rich” to qualify for help.

A parent making $40,000 – $70,000 in New York City is not wealthy. Those families are not comfortable. They are not secure. They are often one emergency away from collapse. And yet they are heavily taxed to fund the very systems from which they are excluded. This is where fairness becomes complicated and nuanced.

Support during hardship is one thing. But when someone has remained officially “poor” for many years or decades, fully embedded in multiple assistance programs, while others work continuously with no safety net, it is reasonable to ask difficult questions. At what point does a system designed to help people get back on their feet risk locking them in place? And at what point does that become unfair to those who are doing everything society asks of them?

This is not about blaming individuals. It is about designing policy that does not unintentionally reward permanent disengagement from work while penalizing effort and honesty.A childcare program meant to strengthen the economy should support work, not quietly undermine it. It should help people move forward, not trap them in static categories that benefit some while exhausting others.

A strong idea that demands careful execution

For this initiative to succeed — economically, politically, and morally — several principles must guide its implementation:

- Reimbursement must be cost-based, not politically convenient, and indexed to real living costs.

- Providers must have income stability, with predictable payments and protection from enrollment volatility.

- Eligibility should avoid hard income cliffs, so families are not punished for earning more or accepting raises.

- Oversight should prevent abuse without criminalizing honesty or survival, both for families and providers.

- Support must accompany regulation, especially for home-based providers asked to meet public-system standards.

None of this contradicts the spirit of free childcare. In fact, it is what gives that spirit a chance to endure. I supported Zohran Mamdani’s vision because it spoke to a reality that cuts across ideology: affordability. Today’s announcement is a meaningful step toward that vision.

But bold promises require equally honest design. Free childcare can transform lives if it does not rest on invisible labor, exclude working families, or create cycles of dependency instead of mobility. Getting this right means refusing to romanticize sacrifice and insisting that fairness applies to everyone involved: parents, providers, and taxpayers alike.

Today was the beginning. What follows will determine whether this promise becomes a durable public good or another well-intentioned idea strained by reality.