If only citizens can vote, why is voter ID controversial?

The debate around the SAVE America Act and Voter ID has moved from a technical discussion about election rules into a broader political battle that is now shaping the national agenda.

President Trump has made the bill a personal priority, publicly pressuring House Republicans to pass it. In the Senate, the bill likely faces a Democratic filibuster, prompting some Republicans to float reviving a talking filibuster. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer has accused Republicans of trying to revive “Jim Crow–type laws,” arguing that the SAVE Act would roll back voting rights rather than protect them.

But What struck me most is not simply how polarized this conversation has become, but how little I actually understood about how voting currently works in the United States before this moment. For years, I’ve known that even green card holders could not vote and had to wait until they became citizens. I also assumed, without questioning it, that there were already clear and consistent systems in place to ensure that only American citizens participated in American elections. The fight over voter ID and the SAVE America Act forced me to confront the fact that this assumption was incomplete.

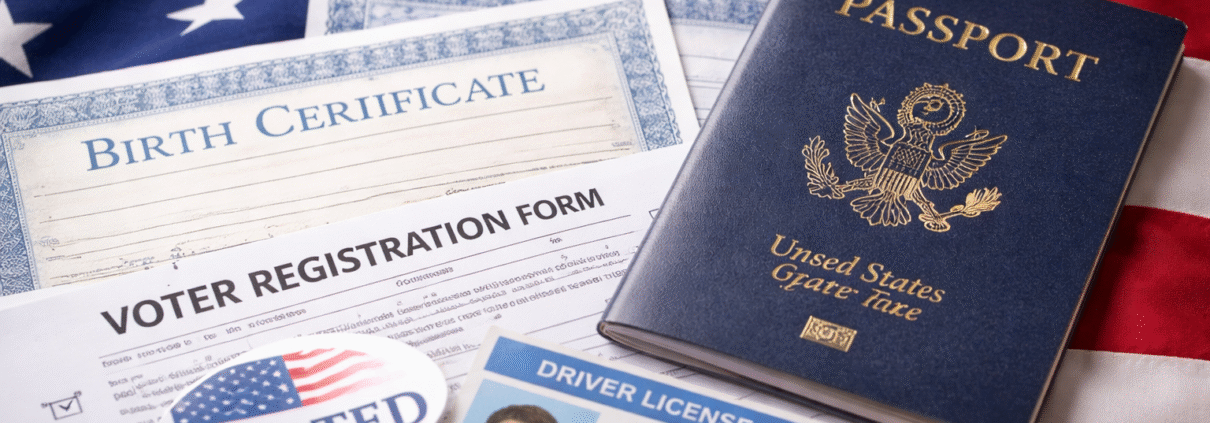

Let’s start with something everyone agrees on: under U.S. law, only American citizens can vote in federal elections. Since 1996, it has been a federal crime for noncitizens to vote, punishable by up to one year in prison. Voting is not just a formality. It is tied directly to what it means to be a citizen. Yet the way this rule is enforced is far less strict than I had imagined. In most states today, when someone registers to vote, they are not required to present documentary proof of citizenship such as a passport or birth certificate. Instead, they sign a statement affirming that they are a U.S. citizen under penalty of perjury. On Election Day, some states require identification, while others do not. Even in states that require ID, that identification usually proves who you are, not that you are a citizen. A driver’s license, for example, does not establish citizenship. In practice, this means the system relies primarily on people telling the truth when they register, and the possibility of punishment later rather than verifying citizenship upfront.

This is the context in which the SAVE America Act has become so controversial. At its core, the bill proposes a more straightforward system: require proof of citizenship such as a passport, birth certificate, or REAL ID indicating citizenship to register to vote, and require photo ID to vote in every state. It would also largely eliminate mail-only voter registration by requiring people to present documents in person. There is an exception process for people who cannot immediately provide documents, but the overall standard would be much stricter than what exists today.

Supporters of the bill argue that this is simply common sense. And I am increasingly inclined to agree with them. If voting is reserved for citizens which it legally is, then asking for proof of citizenship should not be controversial. To me, that is not partisan. It is basic logic. We require proof of identity and eligibility for far less consequential things every single day, yet when it comes to choosing the leaders of a country, suddenly this becomes “extreme.”

Opponents warn that stricter requirements could disenfranchise millions of legitimate voters who may not have easy access to documents like passports or birth certificates. They argue that many elderly, rural, or low-income Americans could be unfairly excluded. I take that concern seriously because access matters in a democracy. But this is where I part ways with much of the opposition is that just as noncitizen voting is statistically rare, I also believe that Americans who genuinely want to vote but are completely unable to obtain any form of identification or proof of citizenship are also rare. In everyday life, ID is already required for so many ordinary activities: opening a bank account, boarding a plane, getting a job, entering many buildings, receiving medical care, picking up certain packages, and even buying alcohol at a bar. So when I hear that there is a massive population of Americans who function in society but somehow cannot obtain a single document proving who they are, I find that very difficult to accept.

Even if we assume that some people would struggle, I do not think the solution should be to abandon reasonable safeguards altogether. If the concern is that some Americans might not have easy access to documents, then the rational response is not to weaken election integrity, it is to make those documents easier, faster, and cheaper to obtain. We should put mechanisms in place to help people retrieve their birth certificates, get state IDs, or passports. Provide assistance, reduce fees, expand access points, and simplify processes. That, to me, would be the sensible compromise.

It is also important to be clear about the trade-off. Recent audits in several states have found real instances of noncitizens on voter rolls, and in some cases, evidence that a limited number may have cast ballots. These numbers are small relative to the overall electorate but they show that the issue is not imaginary. So we are weighing two risks: that of election fraud, and a risk of eligible voters facing hurdles. Between those two, the choice feels like a no-brainer to me. I think it makes more sense to tighten safeguards to protect the vote, while helping people get the documents they need, rather than leave a loophole in the system. If citizenship is the foundation of voting rights, then proof of citizenship should carry real meaning.

Ultimately, this debate is not just about paperwork or party politics. It raises deeper questions about what voting represents, how much trust we place in our institutions. So I end with a genuine challenge to readers: if you oppose voter ID and proof of citizenship requirements, explain your position in good faith. Is it that you are comfortable with some noncitizens voting? That you believe there is no real risk of that happening? Or do you truly think so many Americans are unable to get basic documents that stricter rules would be unjust?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!